Shell companies are known to be misused by individuals and companies for the purpose of avoiding taxes as well as to launder money. Investigations reveal that shell companies are amorphous entities. Learning from the experience during demonetisation, large number of shell companies allowed the laundering of cash by providing entries that helped convert black to white. In this context, the government set up the Task Force earlier this year in February. The Task Force is to adopt a “Whole of Government Approach” where different government agencies such as Enforcement Directorate (ED), SEBI, and Ministry of Corporate Affairs (MCA) as well as Income Tax department will take co-ordinated action. Recognising the illicit activities perpetrated by shell companies, efforts to weed out such companies are welcome. While such concerted effort is being made there exists no definition of a ‘shell company’, i.e., none of the existing laws define a ‘shell company’.

Definitional issues

As mentioned earlier, the characterisation of shell companies is an arduous task. However, to begin with, it is important to isolate the various kinds of shell companies. Firstly, a shell company can be a dormant company with assets on books showing little or no economic activity. Such a shell company, as defined by Her Majesty's Revenue and Customs (HMRC) can be a “company held by a company formation agent intending to sell it on”. Alternatively, shell companies can be used to launder money through a series of entries used to convert undeclared money. Therefore, these can be companies with few assets but with reported activity. There are various definitions for ‘shell companies’, which take into account different characteristics of shell companies. For example, the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) in the U.S. “define the term "shell company" to mean a registrant, other than an asset-backed issuer, that has no or nominal operations, and either no or nominal assets; assets consisting solely of cash and cash equivalents; or assets consisting of any amount of cash and cash equivalents and nominal other assets”. Black’s law dictionary defines a shell company as “a firm that does not trade, is formed to raise funds, attempt the take-over, go public or act as the front for an illegal venture.” Similarly, many double tax avoidance agreements (DTAAs) define shell companies to curb treaty abuse. Recently, India introduced, through amending protocols, modifications to its treaties with Singapore (Article 24A) and Mauritius (Article 27A) which contain definitions of shell/conduit companies. The treaty with Mauritius mentions that “a shell/conduit company is any legal entity falling within the definition of resident with negligible or nil business operations or with no real and continuous business activities carried out in that Contracting State” followed by expenditure test. The comparison of definitions of shell company substantiates the point that the entity can have nil or nominal operations. Therefore, the identification of a shell company can be based on the criterion that the company reports little or no activity. Although, shell company can be legal, it being used for illegal purposes must be established.

While setting up the Task Force, the government had put out a press release wherein it provided a parenthetical definition of Shell Company as that which “does not conduct any operations and indulge in money laundering." In the same press release it is stated that “in the initial analysis it was found that ‘Shell Companies’ are characterized by nominal paid-up capital, high reserves & surplus on account of receipt of high share premium, investment in unlisted companies, no dividend income, high cash in hand, private companies as majority shareholders, low turnover & operating income, nominal expenses, nominal statutory payments & stock in trade, minimum fixed asset.” This raises many concerns with regard to the definition. First, is a shell company active or not? Second, considering the red flags are based on an initial analysis, is this the definition adopted or can there be subsequent variations?

Weeding out of shell companies

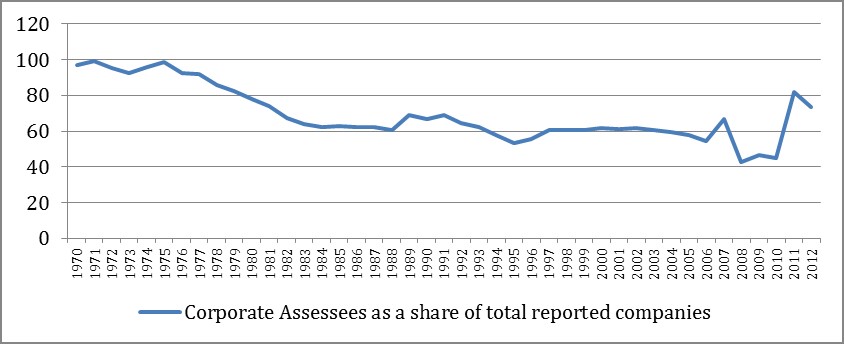

It is claimed that 1.75 lakh “shell” companies have been struck from the register of companies in India. This implies that the definition adopted assumes that the shell company does not undertake any activity. However, there are problems with this approach, not just that there is no explicit definition of a shell company but that the striking off of companies is permissible even in cases where the company may not be a shell. As per the Sections 248 (1) of the Companies Act 2013 the name of the company can be struck off in cases "where the ROC has reasonable cause to believe that: (a) a company has failed to commence its business within one year of its incorporation; [or] (b) a company is not carrying on any business or operation for a period of two immediately preceding financial years and has not made any application within such period for obtaining the status of a dormant company under section 455.” A careful read of the Act reveals that a company that no longer is operating and does not comply with Registrar of Companies requirements may be struck off. Further, a dormant company can well be legal. Therefore, the equivalence claimed between companies that are struck off and shell companies can be incorrect. To illustrate, since the 1970s the number of corporate tax assessees have been less than the registered companies. This means that the companies are still on the register (of companies) but not filing their returns. This gap could simply be because companies are no longer viable and the fact that winding up of a company is a cumbersome process, they choose not to operate. To address this issue fast track exit (FTE) mode was made available in 2011 which allowed companies to be struck off from the register (earlier through section 560 of Companies Act, 1956). After the introduction of FTE in 2011 there is discernible improvement in the ratio of corporate tax assessees (see figure). Further, since the law allows that a company that has not filed for dormancy and ceases to report any activity for two years can be struck off, allows a company that is non-compliant with MCA procedures to be struck off without any application. Therefore, the striking off of companies could mean that there are a set of companies that are no longer viable and have been struck off since they no longer comply with their annual filing requirements.

Source: Estimated using MCA21 data and CAG data on corporate assessees.

The definitional issue has only exacerbated the situation. The MCA, which cannot probe manipulation of penny stocks, in its letter dated 9 th June asked SEBI to investigate 331 ‘suspected’ shell companies. On 7th August 2017, in haste, SEBI applied the Stage VI Graded Surveillance Measure (GSM) on 331 companies on the intimation of MCA. The GSM framework was introduced in March 2017, as per which the GSM can be applied to “securities that witness an abnormal price rise that is not commensurate with financial health and fundamentals of the company which inter-alia includes factors like Earnings, Book value, Fixed assets, Net worth, P/E multiple, etc.” There were two problems with this approach. One, SEBI applied the GSM without investigation, on grounds that it is a ‘suspect’ shell company when the GSM must be applied to cases where the stated objective criteria are met. Two, the definition of Shell Company that the appellants refer to is the ten point criteria, in the press release mentioned earlier, on the basis of which the appellant company cannot be classified as a shell. The SAT gave stay order to 6 other companies based on the lapse in SEBIs approach observed in the case of J. Kumar Infraprojects. Therefore, these cases drive home the point that there exists little or no definitional clarity with regard to shell companies. This is further corroborated by the fact that operational companies are listed as ‘suspect shell’ companies.

There are important conclusions to draw from the recent experience. First, the lack of definition can create confusion. In my earlier work, Tandon (2016), I had shown that if the red flags or criteria to identify a shell company are altered slightly the sample of ‘suspect’ companies can change. For example, if the criteria for identifying shell companies are say expenses, the equivalent of its income, i.e. zero profits and taxes, sporadic reporting of company financials and a PE higher (taking BSE data) than the industry average with an EPS below industry average, I identify 21 companies. Alternatively, if the criteria are zero or no profits, no income from sale of goods and services as well as a registered office which had been reported by at least 20 other companies 12 different companies flagged as shell. Existing definitions, mentioned earlier, can be used to define shell companies in India.

Further, while defining a shell company it is necessary to separate companies that are not active from shell. For example, Stiglitz and Pieth (2016) believe that it may be useful to eliminate zombie entities to be able to trace shell companies. Therefore, striking off companies that do not report any activity may be a helpful exercise but these companies must not be confused with shell companies. There may be companies that no longer report activity but are not set up for illegal purposes. Therefore, a careful investigation is necessary prior to establishing that the said company is a shell.

Way forward

The problem with the ‘whole of government approach’ is that each agency is responsible for investigating a specific kind of irregularity. For example, the power to strike off errant companies and the information of beneficial interest (Section 89 of Companies Act, 2013) is available with MCA, tax evasion can be probed by the Income Tax department and manipulation of penny stocks can be investigated by SEBI. In order to avoid the confusion or overlap, as arose in the case of companies mentioned above, each agency may adopt its own definition of a shell company, may independently initiate probe against ‘suspect’ shell companies and consequently take punitive actions.

The author is Suranjali Tandon, Consultant at NIPFP, New Delhi.

The views expressed in the post are those of the author only. No responsibility for them should be attributed to NIPFP.