The ability of government to shrink the expenditures in 2019-20 would severely strain attempts to maintain fiscal discipline.

This year’s Budget speech was the first I have seen that, in my memory, has no paragraphs on the fiscal situation which, along with the tax proposals, is at the core of any Budget. However, it outlines the contours of government economic policy more generally, and does it well. It also directly addresses concerns regarding the banking and financial sectors with concrete proposals to tackle the currently troubled situation.

In my previous column (Some medium-term fiscal arithmetic, June 7), I argued that the Centre’s fiscal space was severely constrained. It is for this reason, perhaps, that the speech avoids any mention of the macro-fiscal situation. This is understandable: It has not been the tradition in India to confront such difficulties openly.

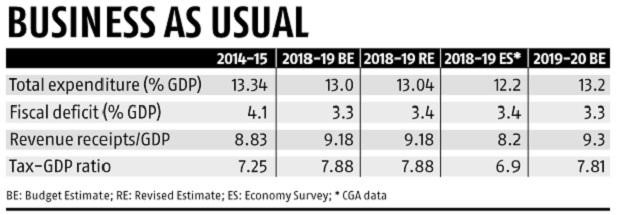

The macro-fiscal numbers presented with the Budget documents suggest “business as usual” (see table). The total expenditure as per cent of GDP continues to shrink from 13.34 per cent in 2014-15 to 13.2 per cent in 2019-20. Revenue receipts increase by only 0.35 per cent of GDP in the same period. Collectively, this has allowed government to secure a fiscal deficit-GDP ratio of 3.4 per cent in the 2018-19 (RE) compared with 4.1 per cent in 2014-15. Thus fiscal consolidation has been secured by consistently reducing the size of the Central government and modestly increasing the revenue-GDP ratio.

This was looking good until I read Table 1, Chapter 2 Vol II, of the Economic Survey (ES). There, the provisional accounts for 2018-19, as reported by the Controller General of Accounts (CGA), has presented data that is very different from those in the revised estimates (2018-19 ES in Table). According to the CGA data, the revenue-GDP ratio is 8.2 per cent, a full percentage point lower than reported in the revised estimates. But the ES pegs the fiscal deficit at 3.4 per cent, the same as in the revised estimates. How is this done given the stunning shortfall in the tax-GDP ratio? Well, the total expenditure-GDP ratio reported in the ES is 0.85 per cent of GDP lower than the 2018-19 (RE). The remaining 0.15 per cent is secured by assuming a slightly higher GDP growth rate than that used in the 2018-19 (RE).

This is worrying. If the survey is correct, it is most certainly not business as usual. The Central government would have shrunk by 1.1 per cent of GDP since 2014-15. Our revenue performance would be dismal compared to previous years. The ability of government to shrink the expenditures by 0.85 per cent of GDP in 2019-20 (as opposed to increase it by 0.15 per cent relative to RE 2018-19) would severely strain attempts to maintain fiscal discipline. For the 2019-20 (BE) to be credible, revenue receipts would need to rise by a whopping 1.1 per cent of GDP, where the Budget allows for just a 0.12 per cent increase.

The CGA is the authorised institution to issue fiscal accounts. If their numbers, as reported in the ES, are way off the mark, then this would cause a collapse in the credibility of the fiscal accounts. But I have full confidence in the fiscal accounts. However, if they are accurate, this would mean that the Budget numbers presented severely underestimate the magnitude of the unstated fiscal crisis that we went through in 2018-19, which cannot be conceivably be fully reversed in 2019-20. At the heart of the crisis is a shortfall in tax revenues which, as the ES makes clear, is mainly due to a shortfall in GST revenues (but also personal income tax revenues), compared to the numbers presented in the RE.

For the rest, the share of central sector schemes is projected to increase from 10 to 13 per cent of total expenditure in FY 2019-20. This will be achieved by reducing the share of subsidies, finance commission transfers and the states’ share of central taxes. The first is laudable, the second not alarming — such transfers taper off in the final year of the Finance Commission award. The third continues an undesirable policy of raising revenues through non-shareable cesses, a predictable, if misplaced, response to the grave fiscal constraint the Central government is facing.

On the revenue side, the share of GST will decline from the projected 23 per cent in the Budget 2018-19 to 19 per cent in the Budget 2019-20. This reflects reality: The GST is not revenue neutral, and the political bargain to get the states on board with GST involved a generous compensation for their shortfalls. This means that the Centre has had to bear the entire brunt of the deficit in GST collections. This has been a costly price in loss of fiscal space that the Centre has had to pay to implement GST. It is now of the first importance that we reiterate our commitment to this important reform and all stakeholders work to improve the effectiveness and buoyancy of GST: The finance minister’s speech proposes important simplifying reforms.

Paragraph 103 of the Budget speech is brief but marks a major shift in government fiscal policy. It proposes that the sovereign government of India borrow from foreigners to finance its expenditures. I have grave concerns about this proposal on grounds of economic security and sovereignty, and about the macroeconomic consequences. But there are no details in the Budget and it would be unfair to comment until the concrete policy proposal is made explicit. But I would respectfully urge transparent reflection and consultation before taking this route.

The author is Director and CEO, National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, NIPFP, New Delhi. Click here for detailed profile.

The views expressed in the post are those of the author only. No responsibility for them should be attributed to NIPFP.

This article was published in Business Standard on July 06, 2019.