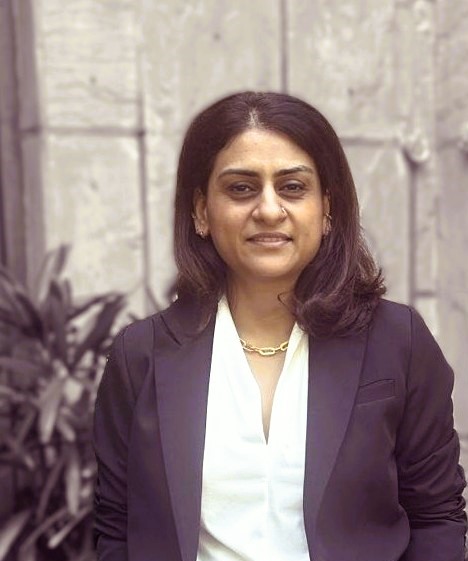

(co-author : Abhijeet Singh, Lawyer and Research Fellow, NIPFP)

Alternative Investment Funds (AIFs) are pooling vehicles that provide an opportunity to invest in unlisted securities and to diversify portfolio. While these offer new avenues for investment, there are liquidity and volatility risks unique to the asset class. Although AIFs have gained traction in India, there is interest in expanding institutions that can invest in these funds. Among the regulatory changes that have facilitated this is the RBI permitting banks and NBFCs to invest in AIFs, albeit with regulatory conditions. However, this led to the unintended ever-greening of loans, which can contribute to financial fragility.

This piece unbundles the regulatory developments and investment policy of AIFs which had recently been under the scanner of the RBI. It also unpacks the key elements necessary for AIFs’ wider acceptability, both institutionally and for the wider retail segment of investors. Then it goes a step further to suggest that if AIF units are acceptable as investment alternatives for more traditional RBI regulated entities, is it time to consider entry of retail investors. It reviews the regulatory considerations for facilitation of retail investments.

What are AIFs?

AIFs are no recent innovation, they have existed for a long time but their journey in Indian financial markets was formalised more recently. These privately pooled vehicles were created for easing investments in early stage and unlisted investments. SEBI introduced the AIF Regulations[1] in 2012 that replaced the venture capital funds regulation, since different kinds of funds operate in the AIF space beyond the venture capital funds. As per the AIF Regulations, there are AIF Categories I, II and III. Category I comprises venture capital funds, angel funds, infrastructure funds, SME and social venture funds. Category II include private equity, debt fund, real estate fund and distressed asset fund. Category III includes hedge funds and PIPE funds.

As per SEBI, the maximum value of funds raised in 2025 were in Category II followed by Category III. Funds in Category I that allow for new investment in ventures have thus far been limited but growing. In order to provide a thrust to the market there have been efforts to expand the participants or investors. Especially as the ticket size of investments in AIFs is substantial and would require institutional participation. A typical minimum investment in the AIFs is INR 1 crore.[2]

Table 1: AIF cumulative net commitments, funds raised and investments made as on 31 March 2025 (INR - crore)

|

Category of AIF |

Commitments Raised |

Funds Raised |

Investments Made |

|

Category I AIF - Infrastructure Fund |

19,650 |

8,969 |

7,530 |

|

Category I AIF - SME Fund |

1,219 |

854 |

747 |

|

Category I AIF - Social Impact Fund |

2,121 |

441 |

540 |

|

Category I AIF - Special Situation Fund |

4,161 |

2,381 |

2,300 |

|

Category I AIF - VCF (Angel Fund) |

10,138 |

5,105 |

4,439 |

|

Category I AIF - Venture Capital Fund |

51,794 |

31,623 |

27,375 |

|

Category I Total |

89,083 |

49,373 |

42,931 |

|

Category II AIF |

10,30,041 |

3,66,621 |

3,32,201 |

|

Category III AIF |

2,29,927 |

1,47,435 |

1,63,029 |

|

Grand Total |

13,49,051 |

5,63,429 |

5,38,161

|

Source: SEBI[3]

There have been efforts to raise investments in AIFs through the introduction of new categories of investors. In 2015, the Alternative Investments Policy Advisory Committee (AIPAC) was set up under the chairmanship of N.R. Narayana Murthy to look into the development of the AIFs and start-up funding in India. The committee examined issues that needed regulatory support. Thus far, the AIPAC has submitted four reports between 2015 and 2018. SEBI has, over time, implemented few recommendations of the AIPAC and continues to refer prevailing issues on AIFs to it. More prominently, the first report includes recommendations related to unlocking domestic pools of capital through enhanced investment opportunities for banks in AIFs.[4] Banks could invest in Category II AIFs which include private equity, debt funds, fund of funds, real estate funds and distressed assets funds. Further, they could invest through their subsidiaries in Category III AIF investments. Therefore, a wide range of investments are permissible for banks. This provides an expanded scope of investments where there is excess liquidity with banks.

Banks’ investment in AIFs

At present banks can invest in equity and debt issued by companies and financial institutions, subject to regulatory restrictions. Therefore AIF units are an additional category of securities that the bank can hold in its non-SLR portfolio. However, allowing such investments led to unintended ever-greening of loan assets by banks. In 2023, SEBI identified that banks purchased non-convertible debentures (NCDs) of the banks’ debtor companies or borrowers with the fund of AIFs. The understanding between the banks and the borrowers was that the funds raised through the NCDs were to be used to pay back the loan originally owed to the bank. This allowed for reclassification of the original debt, along with other regulatory obligations such as provisioning requirements.

Figure 1: Banks’ evergreening mechanism using AIFs

Source: Authors’ construct

Acknowledging the prevalence of the practice, RBI issued a circular on December 19, 2023 instructing all Regulated Entities(REs), under RBI, to either exit the investment in the AIF within 30 days or, in case such an exit was not possible, REs were required to make 100 per cent provisions for such investments. Further, the investments by REs in Junior Tranche or subordinated units of AIFs which followed the Priority Distribution Model (PDM) were required to be fully deducted from the RE’s capital funds. A PDM is a waterfall mechanism which allows creation of Senior Tranche and Junior Tranche or subordinated units of the AIFs. The Senior Tranche receives priority in distribution of profits and loss sharing absorption as opposed to the holders of the Junior Tranche or subordinated units.

Later RBI eased this requirement where the provisioning was required to be made only to the extent of the debtor company exposure of the AIF exclusively. The regulation is specifically to curb evergreening of loans and not for the riskiness of the asset per se. Then in a further relaxation equity share investments by AIFs were excluded from the provisioning requirement.

As per the latest draft circular dated May 19, 2025, RBI has eased the regulation to allow RE’s investment limit of 10 per cent of the corpus of the AIF Scheme, that is subject to the proportionate provisioning requirements (as provided in the RBI circular dated March 27, 2024), but now the downstream investments by the RE excludes ‘equity instruments’ which enhances the scope of exclusions beyond equity shares to include compulsorily convertible preference shares and compulsorily convertible debentures of the debtor company. Further, a collective cap of 15 per cent investment by RE in the corpus of the AIF Scheme, has been laid out. Also these restrictions are only applicable if the investment by the RE is above 5 per cent of the corpus of the AIF Scheme, irrespective of the debtor company being a portfolio company of the AIF. This relaxation raises very important questions for regulations.

- On what basis is this 5 per cent limit made considered acceptable and therefore not subject to provisioning where these include AIF Category I and II?

- Instead of such exclusions, ‘tests for evergreening of loans’ as recommended by RBI in the draft circular must be developed. There are different practices across the world for evergreening like bullet loans[5] or zombie lending,[6] where studies have tried to examine the instances of such lending. Then there are general macroeconomic, capital adequacy stress, and credit risk testing requirements by central banks but not explicitly on evergreening.[7] One way is to triangulate existing exposure of company to bank lending, the risk of default for the company (liquidity constraints) and size of fresh lending being considered. Similar reporting is mandated in US in FR-Y14 dataset[8] that compiles loan-level information, banks’ risk assessments for each borrower, in particular firms’ probabilities of default.[9]

- Third, there remains an issue of compliance with RBI and SEBI regulations on investments. This includes enforcement of the 15 per cent overall cap rule which would require the AIF investment management committee, regulated under SEBI, to take discretionary calls on the rule on limits imposed by the RBI. This creates an oversight vacuum dehors any mechanism for inter-regulatory coordination. Besides, RBI may have to pick winners whilst deciding which bank would have to restrict investments beyond the permissible limits in order to meet this overall cap rule.

- If banks can invest their money in AIFs then maybe retail investors may be allowed to invest through funds that facilitate tokenization, in the future. This would fillip the role of AIFs, from being perceived as a vehicle for covering bad loans by banks, to an avenue for making viable investments by the retail investors. This point is further developed.

As mentioned earlier, AIFs are large ticket size investments and it is therefore inaccessible for retail investors to buy these units. If banks can invest, especially during times of excess liquidity it may be useful to explore the option of retail investors that are also depositors to invest in AIF units. Tokenization can be useful for this purpose. It is the process of using the blockchain technology, to represent and maintain the record of ownership of securities such as stocks or bonds.[10] Many jurisdictions have active use cases of tokenization of traditional securities.[11] The concept of tokenization stems from the idea of fractional ownership of assets and securities.

The emergence of Fractional Ownership Platforms (FOPs) for Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) led SEBI to amend certain provisions of its regulations in 2024, in order to accommodate this disruption which increased access for some segments of the retail investors. The REITs’ FOPs are distinguishable from the fractional securities in the sense that, in the FOPs, the investors have fractional ownership of the real estate assets. A Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) is used to create this ownership interest by issuance of securities in the SPV. Thus there is a fractional ownership of the assets and not the REITs’ units. However, in case of fractional securities, the fractional ownership is of the very ‘security’ such as stocks or bonds.

Source: Authors’ construct

SEBI has been keen on introducing fractional ownership of securities in India, however, it would require amendment to the Companies Act, 2013.[12] The Company Law Committee report of 2022, made recommendations for the necessary amendments for enabling fractional ownership of securities whilst citing examples from other jurisdictions such as the United States of America, Canada, and Japan.[13] Thus for AIF units, which were classified as securities in Finance Act, 2021, this would mean a larger exposure to the retail investors, since the AIF Regulations restrict ‘pooling vehicles’ such as the SPVs used in REITs and further limit the number of investors in an AIF Scheme to 1000.Thus fractional securities (potentially using tokenization), if and when allowed in India, may open up the AIF investment route to the larger public.

As the market for AIFs develops, different kinds of regulatory arbitrage may arise. Would it then be worth considering a new class of investors than to add more regulations.

Figure 3: Proposed fractional AIF units model

Source: Authors’ construct

[1]https://www.sebi.gov.in/legal/regulations/feb-2025/securities-and-exchange-board-of-india-alternative-investment-funds-regulations-2012-last-amended-on-february-10-2025-_92424.html

[2] The ticket size for Social Impact Funds(Category I) which invests in listed non-profits is INR 2 lakh.

[5]https://www.bayes.citystgeorges.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/640579/Dassatti_et_al_2021_CBR.pdf

[10]https://www.mofo.com/resources/insights/250512-us-sec-considers-conditional-exemption-for-tokenized-securities