The public budget of a country is one of the earliest economic tools that economists and accountants have had available over the years for their theorizing and their analyzing. Public budgets became available when the public accounts of countries could be separated from the private accounts of those who ran the countries (kings or other rulers).

The early, original budgets were limited in their size and had few explicit objectives to promote. These included national defence, domestic security (with police and justice), some essential public infrastructure, administration, and a few others. Equity objectives generally played very limited if any role in old budgets. The situation started changing in the twentieth century, especially in the second half, when countries became more democratic, and when the pursuit of equity and other social goals progressively entered the public budgets. Access to higher public revenue had also become easier, due to changes in the economic structures and to the growing acceptance of the principle of ability to pay in taxation. These changes made the pursuit of utilitarian objectives more achievable, through public budgets.

Budgets became progressively more ambitious in the goals that they promoted. Budgets became also more detailed documents, and generally more complex. Their marksmanship moved from the abstract concept of the “country” to the more specific one of its “inhabitants”, generally defined as nucleuses of families and with some stratifications among different classed or categories of citizens. The social-utilitarian objective became progressively more important. As time passed, the past uniformity in objectives of public budget started to give way to new considerations. The need to educate the young, and to increase the countries’ “human capital” directed more budgetary attention to the needs of the young. The lengthening of life expectancy, that increased the share of older components of the populations, directed the allocation of some spending to the protection of the old. The breaking up of large, extended families created increasing public needs to deal with invalids and individuals needing special attention.

In countries with individuals from different races, racial equity started to attract attention. In countries with high shares of foreign born, the treatment of immigrants attracted some importance. Finally, the realization that men and women may be subjected to different stresses in most countries, and in some more than in others, could not fail to become an area of interest to the budget. This book is especially focused on the roles that men and women play in the economies of many countries and in the ways in which budgets have ignored or have accommodated those roles. It provides the most comprehensive survey now available of what is known in this area and on what has been achieved so far in several, different countries, including India.

“Gender budgeting” has become progressively more common in the world but the author argues that it has not become common enough. Many countries’ budgets continue to implicitly discriminate against women, especially in some countries, and especially in developing countries.

In some of these countries, women have often responsibilities within families that demanding but are not officially measured. These responsibilities may include having to get drinking water or fuel for burning from far away sources. Because of these burdens, girls often are not able to attend schools thus making more difficult for them to raise their life incomes. In these cases, public spending that provided families with running water and burning fuel would remove this significant “gender bias”. But such cases would require higher public resources. Thus often difficult choices must be made. The choices must pay attention to gender considerations.

The eleven chapters that form this book are full of information on these issues and on attempts by various countries and by some sub-national jurisdictions to deal with gender-relevant issues in their budgets. The book provides a lot of statistical evidence and useful discussion of the connection between gender budgeting and the UN sustainable development goals. The book recognizes that the “mechanism design” that is needed to achieve various social goals is often inadequate and need reforms. Sen’s concern about the many statistically “missing women” in countries such as China and India also attracts some discussion.

The book highlights the difference between “ex ante gender budgets” and “ex post gender budgets”, recognizing that inefficiency or even corruption may distort the budgetary interventions away from the original intentions. Australia is mentioned as having been a pioneer in developing a gender-sensitive budget statement. The need for using a “budget lens” is now increasingly recognized and countries are becoming increasingly aware of the need for such lens. The book reports that as many as 90 countries are now pursuing some form of “gender budgeting”. This trend has created an increasing need for statistics that are disaggregated by gender. Such reliable statistics often do not exist. Lekha Chakraborty’s new book is a welcome addition to an area of public finance that is still relatively unknown to many. It is an area that is likely to grow in importance. This book should help in attracting increasing attention to this area.

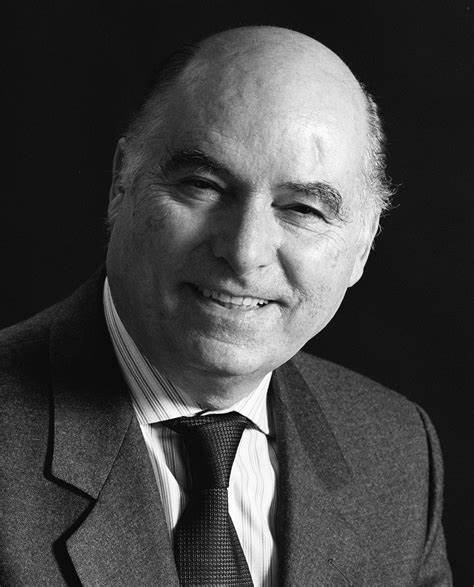

The author is Vito Tanzi, Former director of the IMF Fiscal Affairs Department is an expert economist with extensive experience in academia, government and international institutions. In addition to serving as a senior consultant to the Inter-American Development Bank from 2003-2007, Tanzi has consulted for the World Bank, the United Nations, the European Commission, the European Central Bank, the Asian Development Bank, the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Organization of American States. Click here for detailed profile.

The author is an external contributor and is not an NIPFP member. The views expressed in the post are those of the author only. No responsibility for them should be attributed to NIPFP.